Ah, sweet stet

![]()

On Monday

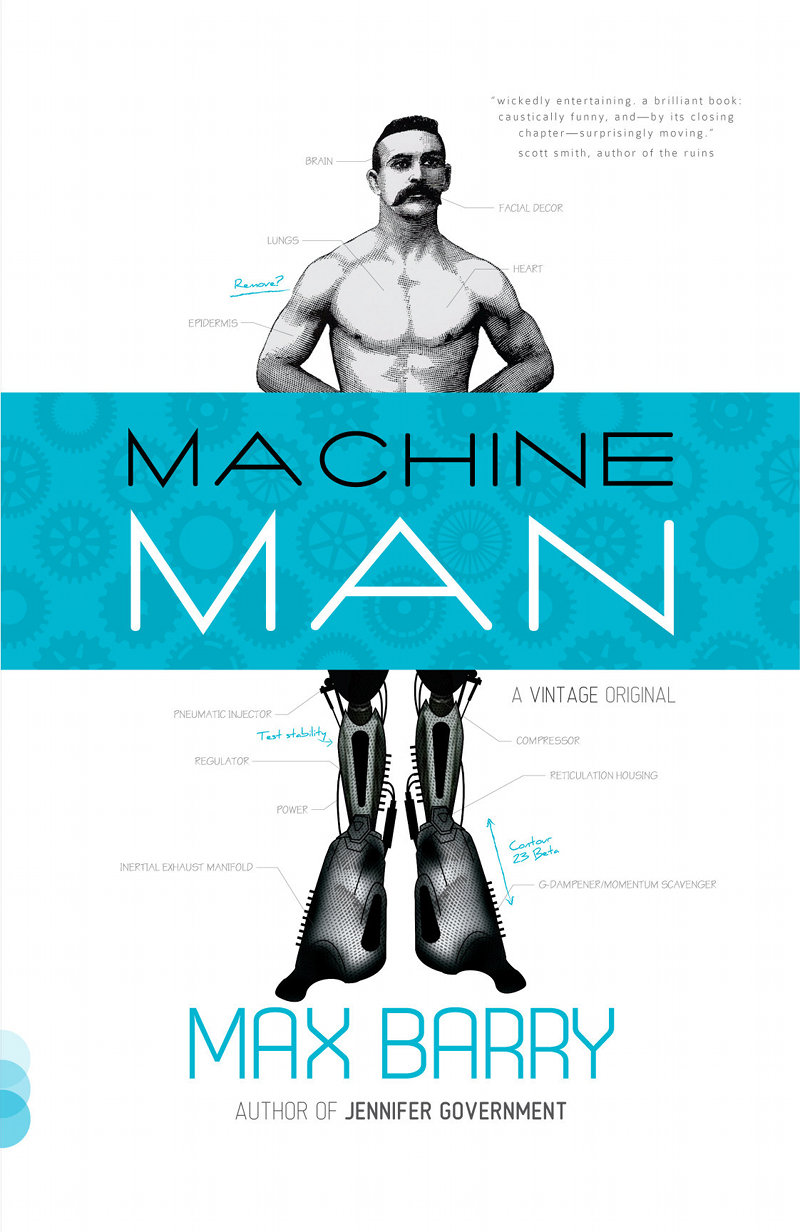

I received the copyedited manuscript of Company.

This means someone at Doubleday has gone through it with a red pencil

and pointed out everything I did wrong: spelling, grammar, continuity,

the fact that someone takes their sunglasses off twice without

putting them back on in between, and so forth.

This is intimidating enough, but on top of that they

do it using arcane symbols that would look more at home if Gandalf

was reading them off a scroll.

On Monday

I received the copyedited manuscript of Company.

This means someone at Doubleday has gone through it with a red pencil

and pointed out everything I did wrong: spelling, grammar, continuity,

the fact that someone takes their sunglasses off twice without

putting them back on in between, and so forth.

This is intimidating enough, but on top of that they

do it using arcane symbols that would look more at home if Gandalf

was reading them off a scroll.

Fortunately I know a little Elvish, so I can usually work out what they’re saying. And they’re mostly right, so I tend to leave their changes alone. But if I want, I can overrule them, with the awesome power of STET. “Stet,” I discovered while editing my first novel, means, “Put everything back just the way I had it.” (Accompanied, one suspects, by the subtext: “Idiot!”) How good is that? When I discovered this word, it was like a gnawing, hollow place in my heart had finally been filled. Looking back, I can’t work out how I ever made it through a day without it. “Max, I tidied up your desk for you.” “No! Stet! STET, dammit!”

Copyediting also reminds you just how archaic the publishing process is. When I write a novel, I use a word processor, nice, proportional fonts, curly/smart quotes, etc, so it looks more or less like the final book. But for submission to my editor, I have to strip all this out, double-space it, change the font to that butt-ugly Courier, and, get this, convert the italics to underlines. This manuscript then gets scribbled on by various people (that’s me in the green pencil), and finally some poor schmuck types it all back in, thus creating a document that looks near-identical to the one I had to start with.

You wondered why it takes 12 months for a book to get published, right? I used to, too.

Caring about Copyright

![]() I was pretty sure that nobody gave a stuff about copyright, but my

last blog

got quite a big response, so either lots of people care about it,

or only a few do, but they all have internet access. There was much

challenging of my argument that copyright should last just ten

years, so, in the time-honored tradition of half-assed essayists

everywhere, I have decided to Q&A myself.

I was pretty sure that nobody gave a stuff about copyright, but my

last blog

got quite a big response, so either lots of people care about it,

or only a few do, but they all have internet access. There was much

challenging of my argument that copyright should last just ten

years, so, in the time-honored tradition of half-assed essayists

everywhere, I have decided to Q&A myself.

(And this is totally irrelevant, but I notice it’s always more fun to write the questions than the answers. It must be the same way evil characters are more enjoyable to write.)

“Since you think a 10-year copyright is such a good idea, obviously in four years’ time you won’t mind if I sell my own print run of Syrup.”

If you publish a reprint of Syrup in 2009, you won’t be infringing my rights: you’ll be infringing Penguin Putnam’s. That’s what happens when you sign with a publisher: you grant it the exclusive right to sell copies. I no longer have the ability to put my novels into the public domain.

“Very convenient. When you sell your next book, then, will you insist that your contract lasts only ten years, after which your books enter the public domain?”

What am I, crazy? If I did that, my publisher would become confused and frightened, I would get a lot of e-mails about “the way we always do things”, and when it was all over I would probably be looking at either a much smaller advance or none at all.

“Aha! Sir, you have been exposed! You say it would be a good thing for copyright to be ten years, yet when given the option, you won’t do it yourself!”

Exactly. My argument is not that shorter copyright would be good for artists. I’m pretty sure it would be bad: not terrible, but definitely worse, at least for people like me who create (arguably) wholly original content. My argument is that it would be good for society, and that’s more important than what’s good for authors.

“Why, you greedy, self-centered hypocrite. You admit that you refuse to do what’s best for society, then?”

Yes. I mean, sure, I’m nice: I recycle my glass and paper, I give to charity, and I smile at my neighbors. But I’m not going to work for free, or take a pay cut, just because I think society deserves to have more of my work for less. It would be good for society for garbage-collectors to take a pay cut, too, but I don’t think they toss and turn at nights about the ethics of it.

When it comes to my career, I plan on doing what I think will help it best. There is a reasonable argument that releasing your work for free helps your career, and I partly agree with this, which is why my short stuff is available for anyone to copy, print, and even sell. But I’m not quite at the Cory Doctorow level, which involves putting your entire novel up for free download. If I thought it would be good for me, I’d do it. But I don’t, and there’s no ethical reason why I should. That’s why we need a change in the law: without it, artists and companies will act in their own best interest, and generally that means grabbing as many rights as possible and hanging onto them forever.

Incidentally, on a systemic level I think there’s something seriously wrong with any plan that requires a lot of people to act against their self-interest. It never works, and the people who benefit most are usually those who don’t join in. The monster that copyright has become can’t be killed by a handful of authors valiantly giving up some of their income, and nor should it be. The law has to be changed. Then everyone can be left to pursue life, liberty, happiness, and profit in the usual, capitalist way.

“Max, you fool. If there was a ten-year copyright, film studios would never buy another book. They’d just wait until the copyright expired and make their film while the author slept in gutters and juggled kittens while begging for food.”

Studios can already make film versions of old books without paying the author a cent, and they’re still buying copyrighted books. There are two reasons, I think. First, if a book-based movie gets made for $25 million, the author pocketed maybe $500,000. A 2% saving is not enough to get a studio worked up.

Second, public domain properties are less valuable, because there are no exclusive rights: the studio can’t do merchandising tie-ins, or make a spin-off TV series, or sequels… or, at least, they can’t do so exclusively. The monopoly is what makes rights valuable, and that’s true whether it lasts for ten years, or twenty, or a hundred. There will still be a massive financial advantage in being the only publisher allowed to produce the new Harry Potter book, and the only studio allowed to make the film, even if that right expires in a decade.

“But the idea of a some sleazy publisher cranking out copies while the author gets nothing… it disturbs me.”

Well, the author gets exposure, which is valuable if he’s unknown, because it builds an audience that might buy his newer books. (In fact, if the author is unknown ten years after his first book, he may be the sleazy publisher: he may re-publish his own work.) If, on the other hand, he’s already well-known… well, he probably isn’t starving.

But to me this is largely irrelevant. I know a lot of people believe in the moral right of an artist to control his or her work, but I don’t. If you invent the telephone, you get a twenty-year monopoly; I don’t see what’s so extra-special about Mickey Mouse that deserves an additional century. Besides, if we’re designing a system to encourage the production of creative works, how happy or rich particular individuals within that system get is of no consequence: what’s important is how well the system works.

“I’ve spent ten years trying to flog my novel to publishers. Under your half-baked scheme, it would have no copyright left!”

I’m pretty sure that the copyright clock starts ticking on the first publication of a work, not on the date of its creation. Also, if you substantially revise a work, you get all-new copyright.

Okay, that’s enough on copyright, I promise. We return to the real world next blog.

Writers for Less Money

![]() Last night I was re-reading that Bible of

Hollywood screenwriting, William Goldman’s

Adventures in the Screen Trade,

when I came across this:

Last night I was re-reading that Bible of

Hollywood screenwriting, William Goldman’s

Adventures in the Screen Trade,

when I came across this:

(This) was, ultimately, responsible for the existence of Hollywood. All the major studios paid a fee to Thomas Edison for the right to make movies: The motion picture was his invention and he had to be reimbursed for each and every film.

But there was such a need for material that pirate companies, which did not pay the fee, sprang up. The major studios hired detectives to stop this practice, driving many of the pirates as far from the New York area as possible. Sure, Hollywood had all that great shooting weather. But more than that, being three thousand miles west made it easier to steal.

This morning, I saw this article on how the British government is planning to extend copyright protection from 50 to 100 years. This would bring it more or less in line with the US, which grants copyright until 70 - 95 years after the author’s death—a period extended in 1998 after lobbying from media companies, primarily Disney.

I’m a writer and earn my entire living from copyright, but this is nuts. Copyright has become a corrupt, bastardized version of itself. Rather than serving as a way to encourage creative works, today it’s a method of fencing off ideas and blocking creativity. And some of the companies pushing hardest for new intellectual property laws are the same ones that owe their existence to breaking them.

We invented copyright to encourage innovation: to make it worthwhile for people to create their own artistic works, rather than copy and sell someone else’s. The aim is not to bequeath eternal rights to an idea, or to make artists fabulously wealthy; it’s to provide society with new books, films, songs, and other art. Copyright provides incentive, but the incentive itself is not the point of the law: the point is to encourage creative behavior.

Having a few years of copyright protection is a good incentive. But a hundred years? Or seventy years after my death? (If I live to 80, it will become legal to print your own copy of Jennifer Government in 2123.) There’s no additional incentive in that. There is nobody, and no company, thinking, “Well, this is a good song, but if I only get to keep all the money it makes for the next 50 years… nah, not worth developing it.”

Copyright extensions, of the kind popping up everywhere lately, have nothing to do with encouraging more creative work, and everything to do with protecting the revenue streams of media companies that, a few generations ago, had an executive smart enough to sniff out a popular hit. It’s a grab for cash at the public’s expense. The fact that there is any posthumous copyright protection at all proves that the law is intended to benefit people who are not the original creator: that is, heirs and corporations. The fact that copyright extensions retroactively apply to already-created works proves they’re not meant to encourage innovation. The only reason copyright extension laws keep getting passed is because the people and companies that became fabulously rich through someone else’s idea are using that wealth to lobby government for more of it.

I’d make copyright a flat ten years. You come up with a novel, a song, a movie, whatever: you have ten years to make a buck out of it. After that, anyone can make copies, or create spin-offs, or produce the movie version, or whatever. Now that would be an incentive. You’d see all kinds of new art, both during the copyright period, as artists rush to make the most of their creation, and after, when everybody else can build on what they’ve done and make something new. You’d see much cheaper versions of books and movies that were a decade old. You wouldn’t have the descendants of some writer refusing to allow new media featuring the Daleks, or Tintin, or whatever. And artists with massive hits would be merely rich, not super-rich.

A century-long copyright (in the UK), or a lifetime plus seventy years (in the US) means books, songs, and films created before you were born will still be locked up when you die. During your life, you will see no new versions, no reworkings, reinterpretations, remixes, or indeed any copies at all, unless they are approved by whoever happened to inherit the original artist’s estate, or whichever company bought it.

Media companies are quick to throw around the word “thief” whenever a teenager burns a CD or shares a file over the internet. But this is theft, too, when an artist’s work is kept away from the public for a century. Ten years is incentive. A hundred years is gluttony.

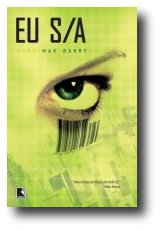

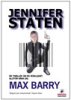

Jen in Brazil

![]()

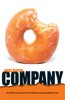

Speaking of covers (no word on what the new Company looks like

yet), apparently the

Brazillian

version of Jennifer Government

is soon to hit the shelves, and they’ve tweaked the design.

Speaking of covers (no word on what the new Company looks like

yet), apparently the

Brazillian

version of Jennifer Government

is soon to hit the shelves, and they’ve tweaked the design.

The title translates as something like, “Me, Inc.”, which I am hoping sounds much less lame in the original Portuguese. They also made the disclaimer look like a Windows XP error dialog box, although I don’t know why. And if you squint, you can see business suit-clad legs behind it. It’s louco!

Update: Apparently a better translation is “U.S., Inc.” That makes more sense.

27 comments

27 comments